I had the pleasure of discovering Huda Fakhreddine’s work a few months ago, just as I set myself the challenge to write more in Arabic. Her articles on the Arabic prose poem were insightful, and so I eagerly awaited her new book. In a way, it could not have come at a better time. The review is followed by personal reflections, the stirrings of my own theories that I am still learning to express, and an ars poetica – a poem on the art of poetry – of my own, which I wrote in the course of reading the book. Enjoy.

Review

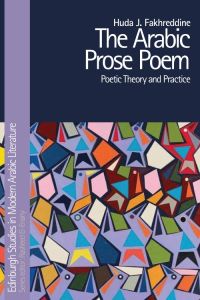

The Arabic Prose Poem: Poetic Theory and Practice by Huda Fakhreddine (Edinburgh University Press, 2021) is a thought-provoking contemplation of the prose poem, which has now occupied a transformative space for some 60-odd years. Well-researched and effectively paced, the book is a great asset for any poet engaging with the Arabic tradition of prose poetry. This review is aimed not at an academic crowd (for I am not in academia), but rather to other poets, particular diaspora Arab(ic) poets, for whom this text offers something useful.

The Arabic Prose Poem: Poetic Theory and Practice by Huda Fakhreddine (Edinburgh University Press, 2021) is a thought-provoking contemplation of the prose poem, which has now occupied a transformative space for some 60-odd years. Well-researched and effectively paced, the book is a great asset for any poet engaging with the Arabic tradition of prose poetry. This review is aimed not at an academic crowd (for I am not in academia), but rather to other poets, particular diaspora Arab(ic) poets, for whom this text offers something useful.

A word on definitions before I begin. Arabic poetry may be distinguished into three main strands: Classical, which is bound by rules of metre and rhyme; Free verse or taf’ila poetry, which is bound by rules of metre; and Prose Poetry, which is not bounded by either. The terminology is complicated by ‘free verse’ and ‘prose poetry’ having different technical meanings in English. I will follow the author’s own terminology and refer to ‘taf’ila’ and ‘prose’ as distinguishing terms.

The book begins its study prior to the inception of the prose poem, in that early 20th century literary impulse which gave us poetic prose and the taf’ila poem. The prose poem, when it enters the scene through the work of Unsi al-Hajj and the Shi’r journal, is mercurial, difficult to pin and define. Fakhreddine explores the idea of ‘churning’ meaning and the appropriation of the Arabic prose tradition to justify the prose poetry movement; the internationalism of the Shi’r poets, and their metaphysical journeys into language reaches its heights, of course, in Adonis. Commentary on his two seminal anthologies, “Diwan al-shi’r al-arabi” (1964) and “Diwan al-nathr al-arabi” (2012) bookend the review of his works, which is centred around his “Mufrad bi sighat al-jam’” (1977). While these chapters present an interesting study of this modernist Arabic poetry, even Fakhreddine sounds frustrated by these intentionally esoteric poets at times (“But making sense of it is torturous and futile”, she writes of one Unsi al-Hajj poem which he himself described as “cursed and cancerous”).

The two chapters that follow (Muhammad al-Maghut and Poetic Detachment; Mahmoud Darwish as Middleman), come as a relief after the time spent with the first generation who made the prose poem their conscious political statement. Al-Maghut’s poetry is unconcerned with achieving esoteric heights of the Shi’r group. He wields “the sword of simile” uncompromisingly, churning out the poetic through his incessant use of this technique. Maghut “mocks the belief that poetry could trigger change” – a philosophical fulcrum around which we might question all the journeys in prose poetry, and what the point of this grand exercise is. Fakhreddin presents al-Maghut’s oeuvre as a sarcastic bulldozing of the gardens of prose poetry tended by Adonis and al-Hajj. Just as think we understand the concepts Adonis has to offer, al-Maghut strips them away and leaves us naked in a storm.

Darwish, then, offers an antidote (or a coat). He was not a prose poet, being one of the seminal masters of the taf’ila poem. But his ambivalent experiments with the prose poem in his final years prove a transformative moment in Fakhraddine’s text. Darwish never names his experiments as prose poetry. In his quest, he provides us with a definition of poetry: “‘It is that which once we hear or read drives us to say: This is poetry and there is no need for proof’ … Poetry can only be achieved after the fact, that is the poem.”

This definition of poetry liberates the prose poem from the political stand of its first proponents and allows it to exist as a type of poetry in and of itself. With that, the text enters its final third, to explore the final destruction and reconstruction of prose poetry through the experiments of Salim Barakat, Wadi’ Sa’adeh and the third generation of prose poets.

Salim Barakat (whose chapter is subtitled “Poetry as Linguistic Conquest”) prepares us for the internet age. A Kurd writing in Arabic, he appropriates and twists the Arabic in ways that perhaps only one whose identity has been subsumed by a colonising language can. His evocative and multi-layered language demands the companionship of a dictionary. “Barakat’s excavations in Arbaic conjure up the language’s thinking process, its webs of associations and its entire history, sometimes in a single word.”

This brings us to the final chapter, centred around Wadi’ Sa’adeh and the third generation of prose poets. We are brought racing into the 21st century, first through Wadi’ Sa’adeh’s transient and silent language, finally into the contemporary multilingual poetry of Golan Haji (another Kurd working through the Arabic language). But these latter poets are liberated from a specifically Arabic quality of poetry. Their poetry is an abstract poetry, almost universalistic, that could be expressed through any language, but they have chosen Arabic (or rather, Arabic has chosen them). An analysis of Haji’s poetry sees out the final chapter, Fakhraddine exploring his poems co-translated and co-authored into English with other poets. These poems exist in a moment of translation; they were not conceived of solely in Arabic but translated, even at the moment of initial drafting from the author’s pre-linguistic thought, into their language of choice. “One does not feel anxious about translating this poem from Arabic”, writes Fakhreddine of Abu Hawwash’s After Bob Dylan; but she might have said this of any poem in the final chapter. As a reader versed in the grammar of contemporary English-language poetry, the poetry featured in this final chapter is far easier to engage with than what came before it.

Thus the book ends, having drawn the prose poem through a journey from the politicised modernist beginnings, to an expansive, multilingual ending. The Arabic prose poem is liberated from both the designations of “Arabic” and “prose”, becoming a poem written in the Arabic language. The mercurial nature of the prose poem is never fully resolved: rather, it becomes accepted.

The selection of poets (Unsi al-Hajj, Adonis, Muhammad al-Maghut, Mahmoud Darwish, Salim Barakat, Wadi’ Sa’adeh and Golan Haji chief amongst them) are effectively threaded, contrasted and interlocked with one another. A coherent and credible narrative of the prose poem is presented. However, I was left uneasy by the lack of female poets. Khalida Said, Iman Mersal and Joumana Haddad get brief mentions, but their poetry is never really centred the way their male contemporaries are.

An important foray into contemporary poetry is made, one which I felt was almost a bit too short – the youngest poets featured in this text were born 1978. While Fakhreddine mentions that “most of the poets of this generation grew up speaking an Arabic dialect permeated by English or French slang and the language of TV, the internet, the languages of the global marketplace” – the absence of millennial poets feels notable. But this is a small niggling point: Fakhreddine offers her readers the analytical tools to read the next generation of poets, and provides enough threads for the reader to pick up and continue by themselves.

“This book is one configuration among many possible ones” – so ends Fakhreddine’s book. She uses her Afterword to effectively indicate the other possible configurations (which Fakhreddine has articles engaging with, such as this series).

A page-turner as far as poetry theory can be, with many excerpted poems, confident translations and astute analysis of each poem in turn, it is threaded together by an overarching vision of the prose poem’s journey that is never forced. The connections the reader makes between the chapters and generations feel organic; Fakhreddine is never prescriptive in her own analysis, allowing one to breathe and consider themselves within this poetic tradition.

This last point is an important one for me, because I read this as an Arab poet writing in English. Balancing on the bilingual tightrope, certainty and confidence in one language so often breeds uncertainty and fragility in the other. This book has helped provide some guidance, and I can recommend it to any diaspora poet. It is a thought-provoking and engaging read.

Reflections

These are some of my personal reflections as a poet, drawn out of reading the text. Not a review in itself, yet my own musings on the purpose of the prose poem. I was drawn to Huda Fakhreddine’s work because I have embarked on a personal project of writing more in Arabic. I have spoken about the issue of conflicted tongues previously.

For me, a prevailing question in everything I write is who is this for? And the answer has always been, for my community. Who is my community? That question is mercurial and depends largely on how I choose to identify. But the Bahraini and Bahrani communities are the two which prevail overwhelmingly in my mind.

Arabic prose poetry feels uncomfortable for me. It comes naturally, as I am already an English prose poet. But does it speak to my community, my audience?

In Bahrain, the classical poem is still the master. While we have our own great prose poet in Qassim Haddad, within the Bahraini tradition, the classical poem reigns supreme. In this, we are perhaps typical of the Gulf. There seems to be more community value (though less international prestige) in the works of, e.g, Ghazi Haddad, who writes of the Bahrani experience in classical style.

Is there a danger to being a prose poet who is not grounded in the taf’ila, in metre? Fakhreddine reflects, “this generation’s writings in Arabic may also at times reflect a loss of footing, a linguistic apathy and maybe sometimes . . . incompetence.” I fear the slip into incompetence. The prose poem presents a very useful means of communication, but the tradition relies on patterns of metres and tropes to survive – when one lacks in them, one is split from the community.

Community and individualism are on opposing sides. We live in a neoliberal moment, where governments and corporations are actively destroying community spaces; in the isolation of individuality, we are easily flattened by these forces. This conflict is repeated in the conflict between prose and classical poetry. The prose poem atomises language and claims a word, a letter, a sound is as poetic as an entire metrical foot. But what is left, when you have only a sound? Is it philosophically neoliberal? Solipsistic, even?

Then again, atomised poems can gather together. A shared dissonance ties them together to build a community of their own through a new shared tradition, where poetry is poetry because it is poetry. Prose poetry is nerve-wracking because it claims to begin from nothing every time. You are borne of no tradition except that which you decide to accept as inheritance. The poem has no clear heritage and offers no obvious legacy. But that is not true: it has a heritage, whether or not is recognises it.

The prose poem is the poem of the colonised and post-colonial, the self-consciously disrupted. Perhaps that is why I enjoy the language that sits in discomfort, like Adnan Al-Sayegh’s disgusting metaphor: “حياتنا التي تشبه الضراط المتقطع في مرحاض عام” “our lives sputter like farts in public toilets.” Supposedly unpoetic, we are unravelling constantly.

If one accepts the prose poem as unproblematic, are they accepting a colonial mentality?

In Fakhreddine’s text, Mohammed Al-Maghut’s cynicism is refreshing after Adonis’s naval gazing. But his belief that poetry cannot bring change – perhaps this is true in his context, when poetry was so self involved. Poetry, as all art, exists in its context. Poetry, in itself, is not the inspirer of change, but poetry and art applied effectively and presciently?

I am committed to poetry at this time because I believe I live in a historical moment where poetry can affect a change in my community’s circumstances. I do not think I would be engaged in poetry if it was solely for my own benefit.

Yet if my communities (the Bahraini and the Bahrani) swim in the sea of traditional poetry, what use is the prose poem I write? To what extent is it purposeful? (Perhaps rather than writing prose poetry in Arabic, as I would in English, I should be writing taf’ila in English as one would in Arabic. This is a translator’s conundrum.)

To what end is the destruction and creation of language? For Barakat, the Kurd in Arabic? For me, the Arab in English? What is the point of the Arabic prose poem, when my community’s speech is set to the rhythms of metre and rhyme?

For me, all writing is inherently political, because our lives are politicised, by virtue of being a marginalised person both in the East and the West. A poetry that expresses that marginality, like the madman screaming in the wind, is not enough for me. In my context, a prose poem in Arabic risks expressing a colonised mentality, and doing little else. From this perspective, the Arabic prose poetry remains controversial…

This is not a manifesto – just reflections and musings which Fakhreddine’s text has helped draw out. The tensions between tradition and prose, community and individualism, are ones I’ve been musing on for a while. Perhaps these thoughts are still incoherent and need greater development. But I set them down, and perhaps they’ll be useful, even if only to me. If nothing else, it is a reflection that this book has been an engrossing, meaningful and needed read for me.

Ars Poetica

How else to finish this then through ars poetica? Here is a review that has disintegrated into rambling, and reconstructed itself into a poem. I wrote this poem somewhere between chapters 6 and 7 – between Salim Barakat and the 21st century poets. Some of the words have clearly been borrowed from the poets read. With the disclaimer that my Arabic’s quality is still a point of development for me, it seemed to me no better way than this to see this article out.

في حاجة للكتابة

ما هي فائدة الكتابة؟ رثاء

معذبوا الأرض

ما هي مهمّة الشعر؟ تخلّد

تنهدنا في شوط البط

الّا تكتب التقليدي أي الحر أي النثر؟

بل يعتمد على جسد الجالية

فانت فرعا منه وشعرك دليله

كن:

الراعي والرعية

العنكبوت، فخور بما ينسج

الغريب، فاقد الفهم

والحروف: اجعلهم أصحاب مجلسك

المعطر ببخور ذكريات

العظام العظيمة

The Need to Write

What is the point of writing? To lament

the Wretched of the Earth

What is the mission of poetry? To immortalise

our sighs in the Era of the Ducks

Do you write traditional, free verse or prose?

Well, it depends on the community’s body,

for you are a limb and your poetry, its evidence

Be:

The shepherd and the sheep

The spider, proud of its weaving

The stranger, incomprehensible

And the letters:

Make them the courtiers of your majlis,

perfumed by the incense of the memories

of the brilliant bones